Switzerland is landlocked, but it has the giant markets of Germany and Italy on its doorstep and is able to sell goods to their rich consumers.

The other three are being landlocked, especially when the neighbouring countries are also poor abundant natural resources and bad governance. Joining a rebel movement gives these young men a small chance of riches.'Ĭonflict is one of four 'poverty traps' that the bottom billion will be unable to escape without our help. On average, all low-income countries face a 14 per cent chance of falling into civil war in any five-year period as Collier notes: 'Young men, who are the recruits for rebel armies, come pretty cheap in an environment of hopeless poverty. The continent's history of repeated coups d'etat and civil wars is not caused by a uniquely fractious populace or especially poor politicians, for example, but by poverty. His findings overturn some of the most persistent myths about Africa's decades of failure. On that basis, spending a few million on parachuting in skilled administrators to support the government, bankrolling infrastructure projects or even sending in troops to put down an incipient coup looks like a bargain. He calculates, for example, that the cost of a badly governed 'failing state' to itself and its neighbours in lost economic growth is a staggering $100bn. But this is a deliberately populist, polemical volume, aimed at concerned citizens, not fellow number-crunchers.Īs an economist, Collier's call to arms is founded on hard-headed cost-benefit analysis, not post-colonial guilt or emotional hand-wringing. He has spent decades studying what makes countries win or lose the struggle to escape poverty and the book is peppered with the findings of a lifetime's technical research.

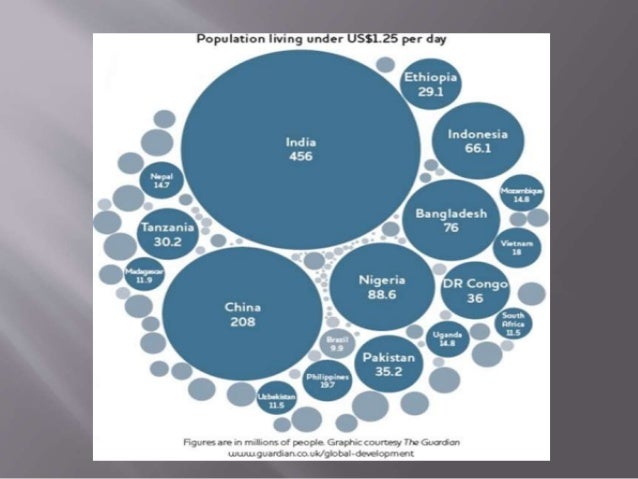

'The countries at the bottom coexist with the 21st century, but their reality is the 14th century: civil war, plague, ignorance,' Collier says. During the Nineties, while globalisation lifted millions out of poverty in China and India, the income of the bottom billion actually fell, by 5 per cent.

In some cases, Paul Collier argues, we may have to send in troops to support democratic regimes, as Britain did in Sierra Leone in 2000, to assist the fragile process of economic development.įor people in the bottom billion, life is getting worse, not better. If the 'bottom billion', the world's poorest people, are to spring the traps that have kept their economies stagnant for decades, Western governments will have to offer much more than money. But according to this powerful book, aid alone will never be enough. In the summer of 2005, it all seemed so simple: tens of thousands of well-intentioned campaigners waggled their white wristbands at Live8 and Bono and Bob Geldof urged the world's richest countries to 'Make Poverty History' by pouring cash into Africa.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)